To what extent is the surrealist description of Hysteria as ‘the greatest poetic discovery of the late nineteenth century’ related to the movements perceived failure to confront issues of desire and sexual difference?’

In the critique on surrealism, the Freudian concept of ‘hysteria’ is posited as being ‘Pivotal to a surrealist poetics and aesthetics of desire#’. So it is highly relevant to the movements’ perceived failure to confront issues of desire and sexual difference. I will try to show how, through the movements tenets to psychoanalysis, contradictions arise in the anti-establishment sentiment proclaimed in surrealist ideology. Because, ‘Psychoanalysis is the creation of the male genius, and almost all who have developed his idea’s have been men#’ then how could the movement have helped to re-align sexual difference and desire, when it is so tied-up in Freudian psychoanalysis- a school of thought limited by its age-old understanding of gendered subject positions in patriarchal society?

Basically, psychoanalysis shows up the one-sided ideas and desires of the male, and as hysteria is diagnosed according to Freudian principles, the surrealist usage of it gives more scope to the movements continuation of the patriarchal and ordered society that it promised to break free from.

The protagonists of the movement in issue 11 of La Revolution Surrealiste, state of the ’hysteria’ condition (which was previously abandoned as a specific disorder) that, ‘Hysteria is a more or less irreducible mental state characterized by the subversions of the relations set-up between the subject and the moral world from which it believes itself to have sprung in practise, beyond any delirious system.#’ The subversion of the conservative relatives in a moral world, is seen expressed by hysterical women- hailed as going beyond the ‘system’ to what is ‘surreal’. But by a male voice- referencing male spectators of females, explaining it as a kind of salvation, even though it is a state reached by undergoing painful hysterical fits. The surrealists’ certainty in the psychoanalytic, male prognosis brings into question the extent of their movements own ‘subversiveness’.

The ‘Uncanny’ is a Freudian term for a central concept to psychoanalysis and therefore also to the aesthetics of surrealism. ‘Uncanny- meaning homesickness, is evoked in understandings of the surreal’# The psychoanalysis of Freud boils down to the anatomical differences between male and female, and this term is applicable to male anxiety about the female genitalia being their primordial source, but also a threat of their own castration once separated from this source. And the ascription of ‘Penis-Envy’ to the female by Freudian psychoanalysis only makes room for the male libido- the female cannot have her own power- everything is related to the penis. The male wants the woman- feels desire for a return ‘home’ but doubly feels agitated at what this desire represents- the giving up of his superiority in the threat of returning to castration- the female threatens his power.

Most of the anxieties experienced by the female are the result of the infantile dawning of a ‘lack’ of male genitalia, which leads to subsequent feelings of insubordination and inadequacy. The failure of the surrealist movement to confront the issues of sexual difference must have a basis in their heralding of Freudian theory. Usefully today however, the female which Freud compartmentalised in his own way, can recognise her insubordination, ‘The psychology of women hitherto actually represents a deposit of the desires and disappointments of men.#’ and from this basis, they add critique that the surrealists can be seen as not only failing in properly addressing sexual differences, but prolonging the misrecognition and misrepresentation of the female. And to show that this argument is not hypocritical, and that this point of view is acknowledged by non-feminists, it is useful to add the male perspective to the misuse of the hysteria- that it is not a way to social revolution, ‘Bretonian surrealism confused decentring with liberation and psychic disturbance with social revolt.#’

Desire is a compound of Seduction and Subversion. The Freudian insight to male desire is that of the seduction of a return to a primordial state#, and the continuing repetition which surfaces at an instinctual level, the subversion away from which may result from the anxiety of the ‘Uncanny’. Seduction is active, and subversion is passive. There is this perpetual flux of the repressed and the its return, and desire, embodies this antagonism. And this is where the poetics of surrealism collides with the psychoanalysis of hysteria, ‘Poetry hinges on the interrelationship between repression and the return of the repressed which the figure of hysteria dramatises.’#

One can see the attraction to cases of hysteria for the surrealists, which in a sense, and occurrence in the context of the asylum, touched on the un-real, ‘Madness is not linked to the world and its subterranean forms, but rather to man, to his weaknesses, dreams, and illusions.’#

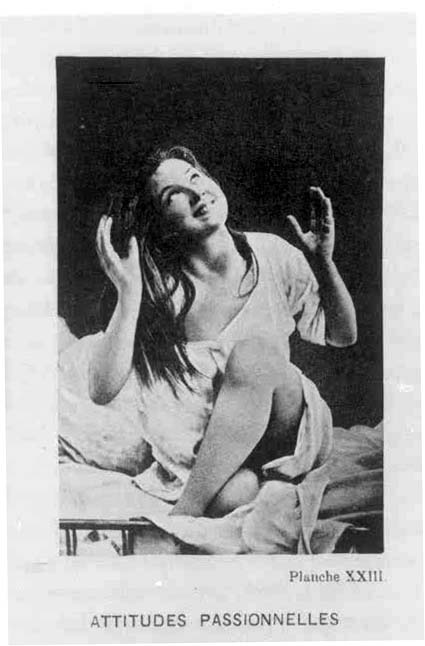

In order to relate the issues of desire and sexual difference visually in surrealist work, we can analyse the iconography of the photographs in an issue of ‘La Revolution Surrealiste’ from 1928# -the more accessible, legible way for the masses to ‘realise psychoanalysis’ radical artistic and cultural implications#’

In order to relate the issues of desire and sexual difference visually in surrealist work, we can analyse the iconography of the photographs in an issue of ‘La Revolution Surrealiste’ from 1928# -the more accessible, legible way for the masses to ‘Realise its radical artistic and cultural implications#’

There are photographs showing a girl in four types of hysterical ‘attack’ and includes textual description of a ‘Clownic’# and ‘Attitudes passionelles’ stage. A young girl, is diffused into stark black background and cartoon-like graphic representation, swallowed in black surroundings, the desirable, possesable woman, is shown in a series of physical contortions. In feminist criticism, the constellation of her limbs has been likened to, ‘The raging beauty of wild beasts in constrained form.’# The eroticised nature of the images is blatant, her hair down and disorderly, and presented in the costume of her bedclothes, the set-up perpetuated upon the patient by her male ‘master’ Doctor is concerning.]

For the Surrealists to reproduce the images, and apply the taxonomy of ’passionate stage’ to the images where the girl looks provocatively at the camera- at the male voyeur, the ambiguous nature of their call for the emancipation of all mankind comes to light. The girl is made the star of ‘hysteria’ and a subject of desire, who pacifies some of the mans guilt for wanting to look with desire through looking as if she invites it. The evil eye, which ‘Represents the gaze as a castrative threat#’ is atoned because this woman is in moments freed from repression- and seems to be euphoric in the moment of her break-down. The un-reality of the scene and surreal quality to the photographs implies the ‘other-worldy’. This looks like a woman acting in her unconscious, ‘The hysteric is in ignorance, perhaps in innocence, but it is a matter of a refusal, an escape, a rejection, and this innocence will soon be renounced as guilt, except that it is unconscious.#’

The surrealist text accompanying this ‘un-masking’ of the sexualised female is falsely laudatory, ‘With its superb aura and its four stages, the third of which captivates us like the purest, most expressive tableaux vivants’# and shows the objectification of the female in accordance with the authority of the male gaze. This is a conservative idea that contradicts the surrealist manifesto, the woman is being punished for the ‘Threat to the patriarchal subject#’

The psychoanalysis of Freud on Hysteria attributes the illness to a sexually traumatic encounter in the patients past history. If the woman is displaying her disconnection from the social system, it is linked to her sexuality- if Bretons statement is true, that ‘Poetry hinges at the interrelationship between repression and the return of the repressed which the figure of hysteria dramatises’ and the study of the condition of hysteria is central to the surrealists aesthetics, then it is an epidemic necessarily used for the sake of the male desires of the surrealists. The woman is necessarily induced into having her attack, which is shown to be traumatic itself, as a re-living of an attack where she is ‘Accusing; they are pointing- with their paralyses, their dyspneas, their knotted limbs. And they point to either the father, a dreadful figure, or to some other male kin.#’

In reality, the hysteric performer is in the ‘Polymorphous libidinal state#’ of her instinctual drives if she is back with that which has been repressed, therefore degenerated to a state of disorganisation. The disturbing case studies which make up Freud’s theory, about the attacks on girls and the pre-sexual age and nature of these repressive incidents are not accounted for in the surrealist article.

She is a pawn in the surrealist manifesto, who has to suffer horrendous abuse to be transformed into some eve-like, transcendental idol of hysteria, pointing to the way out for men, and she is discarded after her contribution to this end is complete, as Helene Cixons notes of Freud’s ’guinea-pig’ Dora; ‘News become scarce. Does she find another Doctor? We don’t know what has become of her but her mythical traces.’#

This surrealist mandate of the support for hysteria in woman is cryptic. Because by the time of the publishing of the third issue of ‘La Revolution Surrealiste’, as a pathological illness it had been found medically redundant- not true, and the ‘illness’ of hysteria had displaced the reputation of Charcot during the process of this realisation. The Surrealists are resorting to a defunct case-the beliefs that women are overtly sexualised but repressed, and with hysteria being so crucially about repression of sexual appetite, the ‘repressed survives in woman; woman, more than anyone else, is dedicated to reminisce.’#

So the Surrealist movement fails to confront the patriarchal order which it claims Hysteria has the power to usurp, ‘Ernst attributed to the actively seductive hysteria the capacity to destabilise or subvert patriarchal power and authority#.’ The character in the cinematographic photographs is not explained as suffering. One can add that this freed woman does not stand for the ordinary woman, and that she is not freed of her own making. The woman has to be deranged in order to contribute to the purpose of a meaningful discourse such as the surrealist movement, and even then she is a ‘Love object’# signifying desire, which is the habit of conservative ideology.

The Surrealists impart the male ‘evil-eye’ - the gaze which puts the woman down- and passes guilt onto her, because she is a threat against it from her penis envy and because she represents a potential castration- which is the entirely disruptive to the patriarchal system.

However they did try to usurp this patriarchal system, and would agree with Freud that hysteria is the result of the repressed bourgeois society, ‘Freud argued that the prevailing social and moral conditions of his age were exacting an inordinately high degree of social repression and in the process were producing a race of neurasthenic men and hysterical women#.’ But on the other hand, the way in which they address the women and put the hysteria theory as the greatest poetic of their age, they appreciate it happening.

Hysteria has a gendered nature- it incites female subordination. If a woman is most free and best inspiration for a poetic when she is expressively in a hysteric episode, then it reduces women to being eroticised, and less aligned to rational thought. The woman is subordinated to the male doctors of psychology and are released from their emotional suffering, through ‘talking it out’ with men- the other ground-breaking Freudian tactic of talking through issues in order. The result is that the Surrealist movement could be accused of only re-formatting society’s consistent ‘Phallic Imperialism#’ coined by Lucie Iriguray.

The key absent issue ignored by the ‘discovery of hysteria as a great poetic‘ - perhaps as a means to the surrealists’ ends, is the painfulness of the experience of hysteria for female patients- and the belief that it is them experiencing their true, unrepressed nature -interpreted as how men see them, and this shows the dichotomy of the surrealist movement. The women are induced into hysteria, a re-living of a trauma, for, ‘Above all, an audience of men; inquisitors, magistrates, doctors- the circle of doctors with their fascinated eyes#’ is how Helen Cixons describes an famous painting of Charcot in‘Grand Hysteria’.

Another point not confronted, is that the women are attention-seeking- and not truly free during these attacks, but acting up as trained by a male audience. Perhaps this is not confronted because it would expose the consortium of doctors at St-Petriere who supposedly conducted sexual relations with the girls-‘Does Freud, who owes so much to Charcot, remember the days when, come nightfall, the patients would either meet them outside or welcome them in their beds#?’

‘This mental state is founded on the need for a reciprocal suggestion or counter-suggestion. Hysteria is not a pathological phenomenon and can in every sense be considered a supreme means of expression.’# The surrealist movements attachment to hysteria as a great ‘poetic discovery’ in a way certifies that it is no illness but a great, sometime euphoric state which is also conducive as a means to their utopian end.

Putting women as resolutely sexualized, and inducing this hysterical state, is so limiting- only from a regression to a suppressed pre-sexual point in some grotty interaction with an exploitative male, can they obtain freedom, as falsely recognised in hysterical states, which are likened by Surrealists, to dreams in the sense of a loss-of-consciousness and the boundaries of everyday life and decorum, ‘The hysteric unties familiar bonds, introduces disorder into the well-regulated unfolding of everyday life, gives rise to magic in ostensible reason’#

For Foucault, the conception of madness since the classical period has been based on the emergence of subjectivity as the locus of philosophical thinking…The modern attitude to madness is based on an understanding of the madman as the subject of his disease.#’ Where the surrealists would argue for the former- ‘Marvellous’, medieval interpretation of madness, and from their studies of hysteria, that madness is almost a gift that offers to women, freedom from societies hegemony.

‘In the middle ages the words of the madmen were not considered to be part of the common discourse, their words were considered to be null and void. Yet their words were also believed to have strange powers, to reveal some hidden truths, predict the future, reveal what the wise were not able to perceive.’ #

It is not for nothing that the main work of Andre Breton is entitled, ‘L’Amour Fou’ - mad love. The very term, ‘Marvellous’ has its roots in medieval etymology,

The Surrealist movement wanted to achieve the ‘marvellous’ in order to rupture the natural order. Mentally ill people were seen as being wise in medieval times, the very same poetic is applied to the hysterical women that are used, in order to import their way of change upon society. ‘The marvellous may even be an attempt to work through ’hysterical’#.

Is it reasonable to suggest that the surrealists wanted to resurrect the ‘poetic’ of hysteria in predicting a future that was free from the subjectivity that emerged from the classical period, and further developed into the social system of bourgeoisie? The answer is, quite possibly, in order for a ‘Re-enchantment of a disenchanted world’.# Most important for the surrealist movement was the abdication of the ’real’ and rational order of capitalist society that stifled ‘freedom’, their main task was to stop the atrophy of the repressive Victorian society. Through embracing all that is unreal, and disassociating from it, because they could not cope with the pre-sexual traumas they lived through, the hysterics were the surrealists poster-girls against moral constraints; ‘We who love nothing more than these young hysterics, whose perfect example is provided by observations relating to the wonderful X.L (Augustine)’#

‘For around 100 years, the western capitalist bourgeoisie has set up shop under the sign of ‘liberty’ and the clearest of its spiritual resources would seem to be used to wash this alluring sign clean of the intellectual and moral stains endlessly accruing to it.’#

In conclusion, the failure of the surrealist movement to confront issues of desire and sexual difference is highly related to their sponsoring of ‘Hysteria’. This movement is new in its use of psychoanalysis. But it still perpetuates a distinctly male narrative, the same order of a patriarchal society that has set-up shop for previous art movements.

The fashion of psychoanalysis at the time seems slightly convenient, and any reading of a surrealist text or film- for instance, ‘The Andalusian Dog’ collaborated on by Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel- the condensed artistic representation of the aesthetic, will present the trope of aggressive punishment of the female by the male.

‘Cars pass at breakneck speeds. Suddenly one of them runs over her, frightfully mutilating her. Then, decisively, as though he had every right to do so, the man approaches his companion, looks her lasciviously straight in the eye (the evil-eye gaze) and puts his hands on her breasts, over her jersey. Close up of the lascivious hands on her breasts…Flattened, terrified, against the wall, the girl watches her aggressor’s manoeuvres. He advances on her…’#

In publishing subject matter like this, and the visual presentations of the female in photography, collage and painting, there is a significant lack of critique that dry’s the mouth when thinking about the surrealists promised enterprise and the actual reality of the Surreal.

# Lomas, David, Surrealism: Desire Unbound, Ch. 2, The Omnipotence of Desire: Surrealism, Psychoanalysis and Hysteria, ed. Vincent Gille, Jennifer Mundy & Dawn Ades, Tate publishing, London, 2001, p.55

# Horney, Karen, p.27, Gender and Envy in Surrealism, ‘The Flight from Womanhood’ ed. Burke, Nancy, Route ledge, NY/London, 1998, p.27

# Louis Aragon and Andre Breton put forward this statement in issue no. 11 of La Revolution Surrealiste, entitled ‘The Fiftieth Anniversary of Hysteria’, Surrealism Against the Current - Tracts and Declarations, ed. Michael Richardson and Krzysztof Fijalkonski, Published by Sterling, London, Pluto Press, 2001, p.143

# Foster, Hal, Compulsive Beauty, October books, MIT Press, 1993, p.5

# Horney, Karen, Gender and Envy in Surrealism ‘The Flight from Womanhood: Some Psychical consequences of the anatomical distinction between the sexes’, ed. Nancy Burke, Routeledge, (New York, London) 1998, printed USA, p29

# Foster, Hal, Compulsive Beauty, p.5

# Compulsive Beauty, Hal Foster states the ‘existence of an instinctual compulsion to retreat- to return to a prior state, p.8

# Lomas, David ‘Surrealism: Desire Unbound’ p.55

# Ferit Guven, Madness and Death in Philosophy, taken from discussion on Michael Foucault, ch 5, ‘Madness and Death in Philosophy,’ State Uni of New York press, USA, 2005, p.126

# recycled from Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot’s studies of hysteria at La Salpetriere Asylum in 1878,

# Lomas, David, Surrealism: Desire Unbound, p.55

# recycled from Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot’s studies of hysteria at La Salpetriere Asylum in 1878,

# Hal, Foster, Surrealism: Desire Unbound , p.5

# Cixons, Helene & Clement, Catherine, The Newly Born Woman, Ch. 3, ‘Sorceress and Hysteria‘, ‘In the schema of hysterical attacks that Charcot traces, the explanation of the ’clownic’ stage is found in the perversion of seducers who, in the grip of automatic repetition which dates from childhood, indulge themselves by seeking gratification in crazy capers and make pratfalls and impossible faces’ I.B Tauris Publishers, 1996, p.12

# Cixons, Helene & Clement, Catherine, The Newly Born Woman, I.B Taurus Publishers, (London) 1996 p.12

# Foster, Hal, Compulsive beauty, p.8

# Cixons, Helene & Clement Catherine, The Newly Born Woman, p.14

# Breton, Andre & Aragon, Luis, The Fiftieth Anniversary of Hysteria: surrealism against the current, tracts and declarations, Ed. And translated bu M. Richardson & Krzysztof, Sterling, Virgina, Pluto Press (published London) 2001, p.143

# Foster, Hal, Compulsive Beauty, p.13

# Cixons, Helene & Clement, Catherine , The Newly Born Woman, p.42

# Friedman, John A. , Gender and Envy in Surrealism, ed. Nancy Burke, Routeledge, N.Y/London, 1998, p.61

# p.5 Cixons, Helene & Clement, Catherine , The Newly Born Woman

# Cixons, Helene & Clement, Catherine , The Newly Born Woman , p5

# Kelly, Julia, Surrealism: Desire unbound ed. Gille, Vincent, Mundy, Jennifer & Ades, Dawn, Princeton University Press, 2001, p.72

# Belton, Robert J. , The Beribboned Bomb- the image of woman in male surrealist art, university of Calgary press, (Canada) 1995, p.33

# Micale, Mark S. , On the ‘Disappearance’ of hysteria: A study in the clinical deconstruction of a diagnosis, article from jstor, ISIS, @1993, The History of Science Society, Published by University of Chicago Press, p.499

# Iriguray, Lucie , The Way of Love, Continuum (London, New York) translated by Bostic, Heidi & Pluhacek, Stephen , p.135

# Cixons, Helene & Clement, Catherine , The Newly Born Woman , p10

# Breton, Andre & Aragon, Louis, ed. And translated by Richardson, M. & Fijalkonski, Krzysztof, Surrealism Against the Current, ‘The Fiftieth anniversary of Hysteria, Breton and Aragon, 1928, p. 143

# Breton , Andre and Aragon , Louis taken from ‘The Fiftieth Anniversary of Hysteria’, Surrealism Against the Current- Tracts and Declarations p.143

# Cixons, Helen and Clement, Catherine , The Newly Born Woman p.5

# Guven, Ferit, ‘Madness and Death in Philosophy’, Ch. 4, p.121

# Rajcham, John, Foucault, freedom of philosophy, (new york) Columbia University Press, 1985, p145

# Foster, Hal , Compulsive Beauty p21

# Foster, Hal, Compulsive Beauty, ch. 2

# Breton, Andre & Aragon, Luis, Surrealism Against the Current, ‘The Fiftieth anniversary of Hysteria, (1928), p.143

# Surrealism against the current- Tracts and Declarations- ‘Poetry transfigured‘, Ed. And translated by Richardson, M. & Fijalkonski, Krzysztof, London, (Sterling, Virginia) Pluto press, 2001, p.148

# Bunuel, Luis, & Dali, Salvador, ‘An Andalusian Dog ‘(1929), ‘Surrealist Literature, Surrealist on Art, ‘About Women,’ p102, ed. Lippard, Lucy R., Spectrum, 1970, printed in USA.

No comments:

Post a Comment